The biblical character Moses

|

| A scene from the Biblical Moses fable of the Torah, and for those who are wondering why I use a brown skin Moses: It's pretty apparent Europeans (Caucasians) didn't dwell in the Nile valley during the so-called days of the Moses fable; additionally, Exodus 4:6 states that God turned Moses' skin "leprous as snow (White) and then returned it to its normal color (Brown)." |

Peace and greetings. I hope these words will greet you in the kindest of manner. This topic, The etymology of Mesu (Moses), has been either overlooked or wholly dismissed in favor of half-truths and supplanted fables with no physical evidence. The purpose of this thesis is to not sway you from your spiritual truths but only to state the absolute facts. Let these validated truths stand upon their merit, and let your soul stand upon its own light.

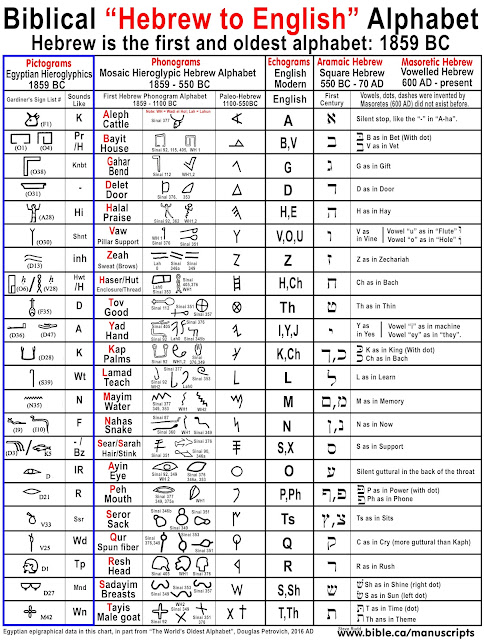

The age of Semitic Morphology vs. the age of ancient Egyptian language

Within the Semitic language family, there are many languages and dialects. Arabic, Tigrinya (spoken in Ethiopia and Eritrea), Amharic (spoken in Ethiopia), Tigre (spoken in Sudan), Hebrew, Aramaic (spoken in Lebanon, Syria, Israel, Iraq, and Iran), and Maltese are the most widely spoken. These languages belong to the Afroasiatic family and are used by over 330 million people across West Asia, the Horn of Africa, North Africa, Malta, West Africa, Chad, and immigrant and expatriate communities in North America, Europe, and Australasia.

It has been discovered that the Semitic languages can be traced back to the period between the 30th and 25th centuries BCE. The only languages that have been attested to be older are Sumerian and Elamite (from 2800 BCE to a later time that is not specified), which are both considered language isolates and Egyptian (from 3000 BCE), which is part of the Afroasiatic family as well.

The Egyptian language is older than any Semitic language. Moreover, several Egyptian words like Amen, Horus, and Ptah are used in the Semitic language family. Egyptologists and Semitists concur that the genetic relation between Egyptians and Semitic is based on morphological evidence.

According to a study on non-Semitic loanwords in the Hebrew Bible, approximately 64% of the 235 loanwords identified in the Hebrew Bible come from non-Semitic languages. Of these loanwords, 135 are from Egyptian.

Source:

(1) Non-Semitic Loanwords in the Hebrew Bible: a Lexicon of Language .... https://docslib.org/doc/4306832/non-semitic-loanwords-in-the-hebrew-bible-a-lexicon-of-language-contact.

(2) Loanwords in Biblical Hebrew - Biblical Archaeology Society. https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/loanwords-in-biblical-hebrew/.

(3) Egyptian Loanwords as Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus and .... https://bibleinterp.arizona.edu/sites/bibleinterp.arizona.edu/files/docs/Noonan.pdf.

(4) Linguistic Dating of Biblical Texts | Bible Interp. https://bibleinterp.arizona.edu/articles/yount357913.

Semites in Egypt took 22 ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs and turned them into the Hebrew alphabet.

The Biblical Moses

In the Torah, it is stated that Pharaoh's daughter rescued infant Moses from the Nile and gave him his name (Exodus 2:10). The biblical narrative surrounding Moses' birth provides a folk etymology that explains the meaning of his name. It is said that the daughter of Pharaoh named him Moses after taking him in as her son. [ מֹשֶׁה, Mōše ], saying, ‘I drew him out [ מְשִׁיתִֽהוּ, mǝšīṯīhū] of the water’".

Transliteration: mōšê

Pronunciation: mo-sheh'

According to Gesenius, considered the Father of the resurrected modern Hebrew language, the Hebrews adapted words from other languages to fit their own language. This includes loan words from the Egyptian spiritual system, as I have demonstrated in previous blog posts.

The name Moses was given by the Pharaoh's daughter, who was not Hebrew but honored the baby with a royal Egyptian name. This name was later redefined the Hebrews.

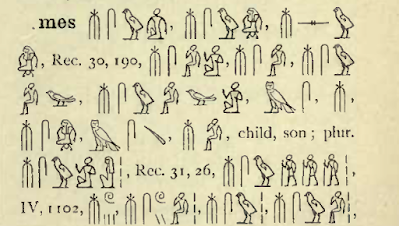

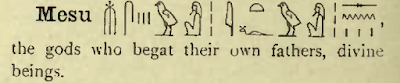

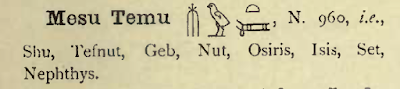

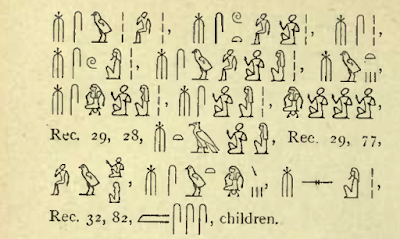

The Egyptian Moses

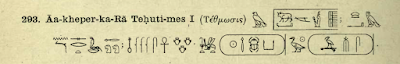

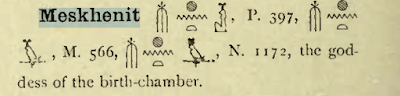

According to the graphic in E.A. Wallis Budge's hieroglyphic dictionary, the name Mesu, which means "Birth" and is equivalent to Moses, was a common male name in ancient Egypt that predates any Hebrew version. The Torah's biblical myth also specifies that an Egyptian woman of royalty gave him the name as a royal title, which is evident in the Egyptian Hieroglyph. The dynasties of ancient Egypt considered Moses (Mesu) to be a royal attribute.

|

| The Egyptian symbol mes means "born of" or "brought forth by." |

|

Mes: 322A/322B

|

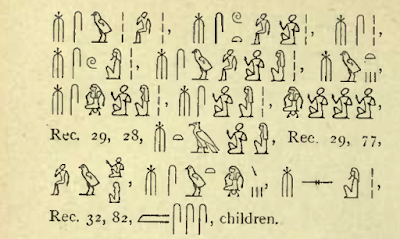

Here are some of the royal attributes associated with MES (: Born Of).

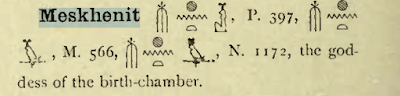

Meskhenit

|

| In ancient Egyptian theology, Meskhenet was the goddess of childbirth. |

|

| Meskhenet merged with a "birthing stone" |

Seqenenre Tao II was a courageous Egyptian pharaoh who governed during the second intermediate period. His name, Seqenenre, translates to "He Who Strikes like Re". He was famously referred to as "The Brave".

Tao II was among the final pharaohs of the 17th dynasty. He presided over southern Egypt while the Hyksos held control over northern Egypt. The Hyksos, who were west-Semitic conquerors, ruled most of Egypt in the 17th century BCE.

It is unclear when Tao II began his reign, but it is believed to have been around 1560 BC or 1558 BC. He governed from Thebes when the Hyksos were in control of Avaris.

Tao II's queen was Ahhotep I. Together, they had two sons who became pharaohs: Kamose, the last pharaoh of the 17th dynasty, and Ahmose I, the first pharaoh of the 18th dynasty.

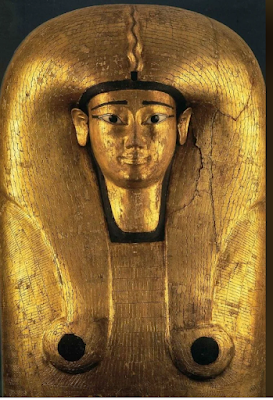

|

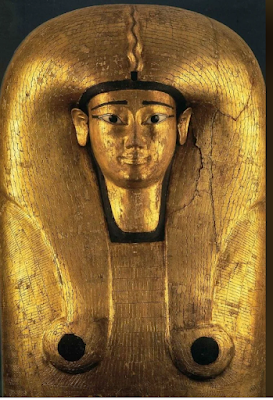

| Queen AhHotep |

|

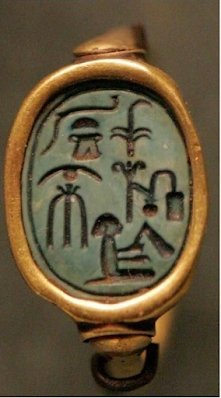

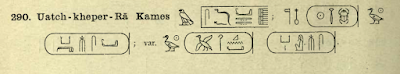

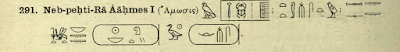

| Signet ring of Queen AhHotep |

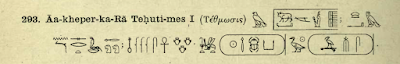

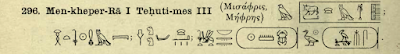

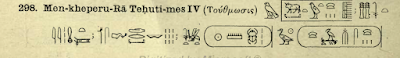

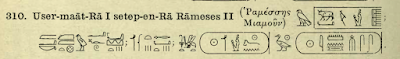

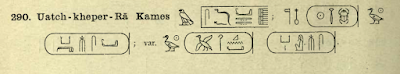

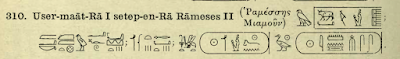

Sampling of "Mes" in The Egyptian King's List

During the 17th to 19th dynasty, the name "Mesu" (Moses) was commonly used, which could have contributed to the creation of the story of the Biblical Moses. According to the tale, a Queen discovered Moses in the water and gave him his name. As an Egyptian royal, Moses' name was not likely to have originated from the Hebrew language.

17th Dynasty

|

| Kamose |

|

|

Kamose (Spirit Born)

|

Kamose was the last pharaoh of the 17th dynasty of ancient Egypt. He ruled for about five years, from around 1555 BCE to 1550 BCE. Kamose was the brother of Pharaoh Ahmose I, who succeeded him and unified Egypt.

Kamose was the last king in a succession of native Egyptian kings at Thebes. The Theban rulers were at peace with the Hyksos kingdom to their north before the reign of Seqenenre Tao.

Kamose waged a successful military campaign against the Hyksos kings to protect Thebes and avenge his father's death. The Kamose Stela tells of this campaign.

|

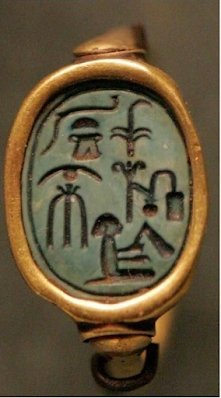

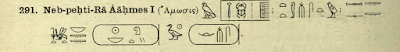

Ahmose l

|

Ahmose was an Egyptian pharaoh who ruled from 1539–14 BCE. He founded the 18th dynasty, the first dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt. The New Kingdom was when ancient Egypt was at its peak of power.

Ahmose I was a member of the Theban royal house. His father was Pharaoh Tao II Seqenenre, and his brother was the last pharaoh of the 17th dynasty, Pharaoh Kamose. Ahmose I was only 10 years old when he took the throne. His father and brother had both died fighting the Hyksos.

Ahmose I's leadership style focused on expanding and unifying Egypt under Theban rule. He expelled the Hyksos from the Nile Delta by adapting a horse-drawn chariot. He also invaded Palestine and re-asserted Egypt's control over northern Nubia.

Ahmose I's birth name was Ah-Mose, which means "The Moon is Born". His throne name was Neb-pehty-re, which means "The Lord of Strength is Re."

|

| Pharaoh Ahmose I |

|

| A ring of Ahmose, which may also read Mes-Iah (Messiah) |

|

| Signet ring of Ahmose I |

|

Mes-Iah (Messiah?)

|

|

| Thutmose 1: Thoth is Born |

|

| Thutmose II |

|

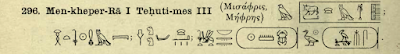

| Thutmose III |

|

| Thutmose IV |

|

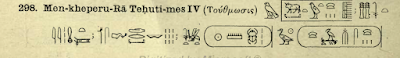

Tut: Horus Name: Ka nakht tut mesut

The strong bull, pleasing of birth.

|

|

|

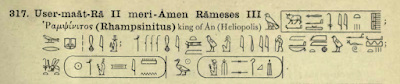

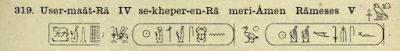

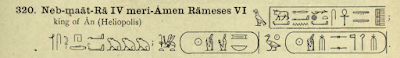

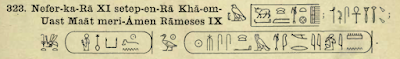

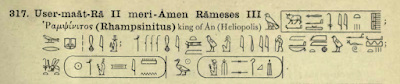

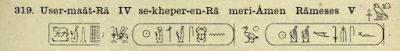

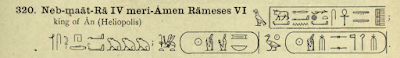

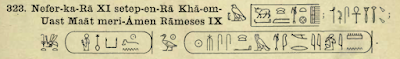

19 Dynasty

|

| Ramesses: Born of Ra |

|

| Ramesses II |

20th Dynasty

|

| Ramesses III |

|

| Ramesses IV |

|

| Ramesses V |

|

| Rameses VI |

|

| Rameses VII |

|

| Rameses VIII |

|

| Rameses IX |

|

| Rameses X |

|

| Rameses XI |

|

| Rameses XII |

The Exodus

.jpeg)

|

| Ahmose I |

Ahmose I, an ancient Egyptian pharaoh, played a significant role in defeating the Hyksos and initiating the XVIII dynasty and the New Kingdom of Egypt. Archaeological discoveries at Tel Habuwa, a site associated with ancient Tjaru (Tharo), shed light on Ahmose’s campaign. Ahmose I led three attacks against Avaris, the Hyksos capital, and had to quell a small rebellion further south in Egypt. After a three-year siege, he defeated the Hyksos by conquering their stronghold, Sharuhen, near Gaza.

The exact number of casualties during the conflict is not known. However, it is estimated that the expulsion of the Hyksos involved a significant number of people. According to Josephus, quoting Manetho’s Aegyptiaca, not fewer than 240,000 people left Egypt with their families and chattels after the treaty's conclusion.

The Tempest Stela

The Tempest Stela, also known as the Storm Stele, is an ancient Egyptian artifact erected by Pharaoh Ahmose I in the early 18th Dynasty of Egypt around 1550 BCE. The stele describes a great storm that struck Egypt, destroying the Theban region's tombs, temples, and pyramids. The stele also describes the restoration work ordered by the kin. The part of the stele that describes the storm is the most damaged part of the stele, with many lacunae in the meteorological description.

The Tempest Stela was discovered in pieces in the 3rd pylon of the temple of Karnak at Thebes between 1947 and 1951 by French archaeologists. It was restored and published by Claude Vandersleyen in 1967 and 1968. The stela consists of a single text in horizontal lines, copied on both sides of a calcite block that once stood over 1.8 meters tall. The side of the stela, termed the ‘face’ or ‘front side,’ had horizontal lines painted red, with incised hieroglyphs highlighted in blue pigment. The reverse face, or back, was unpainted.

The Tempest Stela is an important historical artifact that provides insight into ancient Egyptian history and meteorology. It is a testament to the power of nature and how it can impact human civilization.

The Ten Commandments

|

| A mock stock photo of the 10 Commandments in Hebrew |

According to the Bible, the Ten Commandments are a set of moral and religious laws God gave Moses on Mount Sinai. They are part of the Torah, the first five books of the Hebrew Scriptures. The Ten Commandments are also known as the Decalogue, which means "ten words" in Greek.

However, the Ten Commandments were not the first laws of civilization, nor were they entirely original. Other ancient texts contained similar or identical rules and regulations predating the Ten Commandments. Some of these texts are:

- The Code of Hammurabi is one of history's oldest and most complete written legal codes. It was created by King Hammurabi of Babylon around 1750 BC. The code consists of 282 laws that cover various aspects of life, such as crime, family, trade, and social justice. The code also includes a famous principle of "an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth" as punishment. Some of the laws in the code are similar to the Ten Commandments, such as "You shall not murder," "You shall not steal," "You shall not bear false witness," and "You shall not covet your neighbor's wife."

- The Code of Ur-Nammu: This is the oldest known law code in the world. It was written by King Ur-Nammu of Ur, a city-state in ancient Mesopotamia, around 2050 BC. The code consists of 57 laws that deal with civil and criminal matters, such as theft, murder, divorce, and inheritance. The code also introduces the concept of a fair trial and a presumption of innocence for the accused. Some of the laws in the code are similar to the Ten Commandments, such as "You shall not kill," "You shall not commit robbery," "You shall not commit adultery," and "You shall not slander."

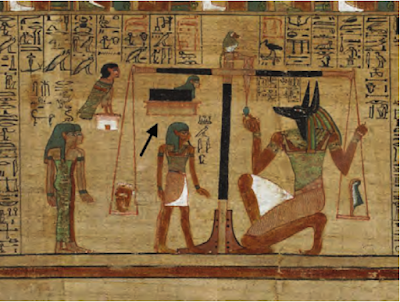

- The Egyptian Book of the Dead: This is a collection of spells, prayers, and rituals used by ancient Egyptians to guide the souls of the dead through the afterlife. It dates back to around 2600 BC and was written on papyrus scrolls buried with the mummies. The book contains a chapter called "The Negative Confession," which lists 42 sins the deceased had to deny before the judgment of Osiris, the underworld god. Some of the sins in the list are similar to the Ten Commandments, such as "I have not killed anyone," "I have not stolen," "I have not lied," and "I have not coveted my neighbor's goods."

These are some similar texts predating the Ten Commandments of Moses. They show that other civilizations nearby had clearly developed equal (if not identical) moral and legal codes long before biblical Moses "received tablets from God" written in the 22-letter so-called Hebrew alphabet excerpted from Egyptian glyphs.

|

| The 42 Negative Confessions likely inspired the creation of the 10 Commandments. |

Did Moses Cross the Red Sea?

|

| A depiction of Moses using wind to part the Red Sea. |

Moses and the Israelites could not have actually crossed the massive Red Sea. At its deepest, the Red Sea is over 8,000 feet deep, 1,400 miles long, with an average depth of 1,640 feet. It's also 190 miles wide at its widest point, meaning it would have taken the Israelites a long time to cross by foot.

Several reasons why some scholars argue that Moses could not have crossed the Red Sea as told in the Torah.

- No archaeological evidence supports the story of Moses crossing the Red Sea.

- The area's geography does not support the idea that Moses crossed the Red Sea. The Red Sea is a deep and comprehensive body of water, and it is unlikely that it could have been parted by a strong east wind, as described in Exodus 14:21.

- There is no historical record of such an event occurring. The Egyptians were meticulous record keepers, and yet there is no mention of such an event in their records.

|

The Red Sea's maximum width is 190 miles, and its deepest depth is 9,974 feet (

3,040 meters), and its area is approximately 174,000 square miles (450,000 square km). |

Moreover, some scholars argue that there are inconsistencies in the story of Moses crossing the Red Sea. For example, Exodus 14:22 says that “the waters were a wall unto them on their right hand and on their left.” This implies that the so-called "Israelites" (no actual written history of that term) were walking through a narrow passage between two walls of water. However, this would be impossible because water cannot stand upright like a wall.

Another inconsistency is that Exodus 15:4-5 says, “Pharaoh’s chariots and his host hath he cast into the sea: his chosen captains also are drowned in the Red Sea. The depths have covered them: they sank into the bottom as a stone”. This implies that Pharaoh’s army was utterly destroyed. However, later in Exodus 15:9-10, it says that “the enemy said, I will pursue, I will overtake, I will divide the spoil; my lust shall be satisfied upon them; I will draw my sword, my hand shall destroy them. Thou didst blow with thy wind, the sea covered them: they sank as lead in the mighty waters”. This implies that Pharaoh’s army was not completely destroyed but only partially destroyed.

Finally, there wasn't any grandeur of victory in the actual event recorded in the ancient texts apart from what was told in the Torahnic orally preserved fable. The Hyksos (Caanaties who were Semiitc and consisted of many ethnicities) founded the 15th Dynasty of Egypt. Still, after they were expelled, all traces of the Hyksos in Egypt were erased by the conquering Thebans (aka Waset). Only a few Hyksos kings are known by name from the ruins of inscriptions and other writings at Avaris (the Capital of the Hyksos while in Egypt) and beyond.

"Yam Suph" (the Red Sea or Sea of Reeds?)

The terms “Sea of Reeds” and “Red Sea” are both English translations of the Hebrew term “yam suph”, which appears in the Bible as the place where the so-called "Israelites" (again, there's no evidence of an Israelite nation in ancient Egypt) crossed during the Exodus. Some scholars argue that “Sea of Reeds” is more accurate, as “suph” could mean “reeds,” “rushes,” or “seaweed.” Others suggest that “Red Sea” is a traditional translation from the Greek Septuagint and the Latin Vulgate. The location of the yam suph is also disputed, as some propose it was a freshwater lake with reeds, while others contend it was a saltwater sea with seaweed.

The 40-Year Biblical Exodus

Joshua 5:6: For the Israelites had wandered in the wilderness forty years, until all the nation’s men of war who had come out of Egypt had died, since they did not obey the LORD. So the LORD vowed never to let them see the land He had sworn to their fathers to give us, a land flowing with milk and honey.

The 40-year Exodus from the Torah is a story that describes how the Israelites left Egypt and wandered in the wilderness before entering the Promised Land. However, this story has been challenged by various scholars and critics who point out some problems with its historical accuracy and plausibility. Some of the issues are:

- No archaeological or textual evidence from Egypt or other sources corroborates the events of the Exodus, such as the ten plagues, the drowning of the Egyptian army, or the mass migration of many Israelites.

- The number of Israelites who left Egypt, according to the Torah, was around 600,000 men plus women and children, which would amount to several million people. This unrealistic figure would have been impossible to sustain in the desert or ancient Egypt.

- The Torah does not explain why the Israelites did not observe the Passover offering for 39 years in the desert, even though it was a central commandment that commemorated their liberation from slavery.

- The Torah does not explain why the Israelites had to wander for 40 years in the desert when the distance from Egypt to Canaan could have been covered in much less time. Some suggest it was a punishment for their lack of faith or a test of their obedience, but others find this unsatisfactory.

- The actual walk from Egypt to Canaan depends on the route, the speed, and the obstacles the travelers may encounter. According to some web search results, the most direct land route is about 160 miles (257 kilometers), and the total straight line distance is about 5270.8 miles (8482 kilometers), which is about 74 days (2 1/2 months) traveling on foot.

These are some of the problems various scholars and critics raised regarding the 40-year Exodus from the Torah. However, not all of them agree on the extent of the implications of these problems. Some may argue that the Exodus story is not meant to be taken literally but rather as a symbolic or theological narrative that expresses the identity and faith of the Israelites. Others may try to reconcile the problems with alternative explanations or interpretations consistent with the Torah. Still, others may reject the Exodus story as a myth or a fabrication with no historical basis.

The eating of "Maana" for 40 years.

Exodus 16:35: The Israelites ate the manna for forty years until they came to settled land; they ate the manna until they came to the borders of Canaan.

According to the Torah, the Israelites survived in the desert for 40 years by relying on God’s miraculous provision of food, water, and protection. God gave them a heavenly bread from the sky called manna, which they collected every morning, except on the Sabbath. God also sent them quail to eat in the evenings when they complained about the lack of meat. God also gave them water from a rock, which followed them throughout their journey. God also guided them with a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night, which indicated when they should camp or move. These are some of the ways that the Israelites survived in the desert for 40 years, according to the Torah. However, some scholars and critics have questioned these accounts' historical accuracy and plausibility and have offered alternative explanations or interpretations.

For several reasons, most mainstream scholars do not accept the biblical Exodus account as historical. It is generally agreed that the Exodus stories were written centuries after the apparent setting of the stories. The historical record offers neither material nor archaeological evidence to confirm the Exodus event.

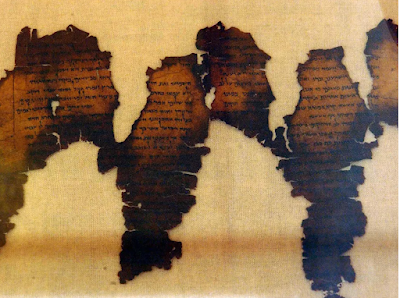

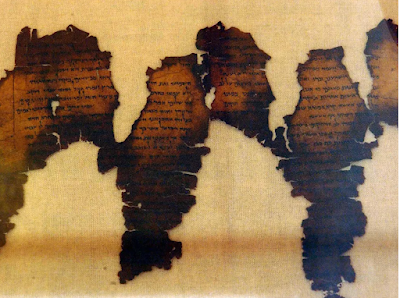

Fake Artifacts and the Dead Sea Scrolls

|

| The Dead Sea Scrolls are now deemed entirely fake. |

In 2020, a study commissioned by the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C., revealed that none of the textual fragments in the museum’s Dead Sea Scroll collection are authentic. The fragments, displayed since 2017, were found to be forgeries made from old shoe leather or other materials in the 20th century. They also include so-called pieces of the Book of Exodus.

Fraudulent artifacts bearing Hebrew inscriptions have been discovered in the past, and some have been used to promote a combined political, scientific, and religious agenda.

In addition to this, Israeli authorities have charged four antique collectors with creating a string of fraudulent Biblical artifacts. The announcement came as police and the Israel Antiquities Authority were ending a large-scale 18-month investigation into antiquities fraud.

The Center for the Future of Museums identified critical issues for museums to address in its TrendsWatch 2019 report. The report highlighted how fraudulent artifacts bearing Hebrew inscriptions were planted to promote a combined political, scientific, and religious agenda.

The Israel Stele

|

A so-called singular instance of the word "Israel".

Found nowhere else, and yet its biblical story is one of victory.

|

The Merneptah Stele, also known as the Israel Stele or the Victory Stele of Merneptah, is an inscription by Merneptah, a pharaoh in ancient Egypt who reigned from 1213 to 1203 BCE. It was discovered by Flinders Petrie at Thebes in 1896 and is now housed at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. The text is essentially an account of Merneptah’s victory over the ancient Libyans and their allies. Still, the last three 28 lines deal with a separate campaign in Canaan, which was then part of Egypt’s imperial possessions. It is sometimes called the “Israel Stele” because some scholars translate a set of hieroglyphs in line 27 as “Israel. The stele represents the earliest textual reference to Israel and the only reference from ancient Egypt.

The so-called name “Israel” is written using three hieroglyphs, which are transliterated by some as “ysr” or “isr.” This particular reading of the hieroglyphs as “Israel” has been challenged by scholars, who state that the name refers to:

- "Jezreel," a city and valley in northern Canaan;

- A continuation of the description of Libya referring to "wearers of the sidelock."

- The term 'Israel' on the stele does not refer to the Israelites of the Bible but to a group of nomadic invaders who were defeated by Merneptah. It claims that the hieroglyphic sign for 'people' is a variant of the 'foreign land' sign and that the determinative for 'country 'must be included. It also suggests that the name 'Israel' derives from a Canaanite god named El rather than the biblical patriarch Jacob.

- The conventional dating of the Exodus to the 13th century BCE is based on the assumption that Ramesses II was the pharaoh of the Exodus. It proposes that the Exodus occurred in the 15th century BCE, during the reign of Amenhotep II, and that Israel had already been established in Canaan by the time of Merneptah.

The Mesha Stele

|

|

Is this Mesha Stele supposedly a replica of the original that was smashed beyond repair?

|

The Mesha Stele, also known as the Moabite Stone, is a black basalt monument from the 9th century BCE inscribed in ancient Hebrew. The inscription tells the story of King Mesha of Moab, who rebelled against the Kingdom of Israel and claimed to have destroyed several towns, including Jericho.

Scholars have argued that the Mesha Stele is not authentic but a forgery created in the 19th century by someone who wanted to support the biblical narrative or make money from selling antiquities. They have pointed out several inconsistencies and anomalies in the stele's discovery, content, and language that cast doubt on its genuineness. Here are some of the main reasons why the Mesha Stele might be a parabiblical forgery:

- The circumstances of its discovery are suspicious. The stele was reportedly found in 1868 by a Bedouin tribe in Dhiban, Jordan, among the ruins of an ancient city. However, the Bedouins did not inform the local authorities or any reputable archaeologist but tried to sell it to various European consuls and agents for a high price. The stele was also broken into pieces by the Bedouins, who claimed that they did so to prevent it from being stolen by rival tribes or foreigners. Some stele fragments were never recovered, and others were allegedly replaced by fakes.

- The content of the inscription needs to be consistent with other sources. The stele claims that King Mesha of Moab defeated the Israelites and conquered several towns, including Jericho (Qeriho). However, no archaeological evidence exists that Jericho was occupied or fortified in the 9th century BCE. The stele also mentions several gods and places not attested elsewhere in ancient sources.

- The language of the inscription is anomalous and anachronistic. The stele is written in ancient Hebrew, but it contains several linguistic features uncommon or unknown in other inscriptions from the same period. For example, the stele uses the definite article (ha-) before proper names, which is rare in Hebrew epigraphy. It also uses some words and expressions borrowed from later biblical Hebrew or influenced by Aramaic. Some scholars have suggested that the forger used a biblical text as a model for composing the inscription but made some mistakes or alterations to make it look more authentic.

There are many more fake Hebrew artifacts, too many to list here, and enough to merit approaching this subject matter with extreme prejudice.

The Ten Commandments Hollywood Movie

The Hollywood movie The Ten Commandments does not portray the Egyptian Exodus of biblical Moses. It is a fictionalized adaptation that takes many liberties with the source material and adds elements not found in the Bible or historical records. Some of the significant inaccuracies are:

- The movie depicts Moses as growing up unaware of his Hebrew origins and having a romantic relationship with Nefretiri, an Egyptian princess. Moses knew his birth family and was nursed by his mother. He also married Zipporah, a Midianite woman, and had no Egyptian girlfriend.

- The movie names the pharaohs as Seti I and Ramses II, but the Bible does not specify their names. The film also confuses the historical roles of these pharaohs, as Seti I was the one who fought at Kadesh, not Ramses II.

- The movie shows Moses killing an Egyptian by strangling him, but according to the Jewish tradition, he killed him by uttering a divine name (Nu Pu Nuk!) that caused his soul to expire.

- The movie omits six of the ten plagues God sent upon Egypt and only briefly mentions them. The movie also does not show the role of Aaron, Moses's brother, who acted as his spokesman and performed many miracles.

- The movie portrays Moses as a charismatic leader and a powerful speaker, but the Bible says that he had a speech impediment and was reluctant to take on the mission.

These are just some examples of how the movie differs from the biblical and historical accounts of the Exodus. The film was influenced by the political and cultural context of the Cold War era and reflected the conservative views of its director, Cecil B. DeMille. It was not intended to be a faithful representation of the events but rather a dramatic and spectacular interpretation. Therefore, it should be taken as something other than a reliable source of information, but rather as entertainment and art.

Rameses II from the 10 Commandments movie and the Torah

Some possible reasons why the XIX Egyptian dynasty of Rameses II could not have been the story of the biblical Exodus are:

- The biblical Exodus is traditionally dated to the 15th century B.C.E [1550 BC—Ahmose I becomes Pharaoh of Egypt], based on the mention of the city of Rameses in Exodus 1:11. However, this city was not built until the reign of Rameses II in the 13th century B.C.E., which suggests that the biblical text was updated to reflect the current name of the city.

- The biblical Exodus describes a large population of Israelites leaving Egypt, numbering about 600,000 men, besides women and children (Exodus 12:37). However, there is no archaeological evidence of such a massive migration or its impact on the Egyptian or Canaanite societies.

- The biblical Exodus narrates a series of miraculous events that God performed to liberate the Israelites from the oppression of the Egyptians, such as the Ten Plagues, the splitting of the sea, the manna and quail, and the water from the rock. However, these events are not corroborated by any historical or natural sources, and they reflect the theological and literary perspectives of the biblical authors.

- The biblical Exodus claims that the Israelites encountered and defeated various peoples and kingdoms on their way to the Promised Land, such as the Amalekites, the Moabites, the Amorites, and the Canaanites. However, some of these peoples and kingdoms did not exist or were not in the region at the time of the Exodus. For example, the Moabites and the Ammonites emerged as distinct groups only in the 13th–12th centuries B.C.E. and the Canaanite city-states were controlled by the Egyptians until the late 12th century B.C.E.

The name Rameses in the Torah

The name "Ramses" (or "Raamses") does appear in the Bible, specifically in the Old Testament. It is mentioned in the context of the Israelites' enslavement in Egypt and their subsequent exodus. For example, Exodus 1:11 mentions the Israelites building the store cities of Pithom and Raamses for Pharaoh.

However, it's important to note that the use of the name "Ramses" in the Bible is considered anachronistic by many scholars. This means that the name was likely used to refer to a location or a period that was familiar to the writers or editors of the biblical texts, rather than being a precise historical reference to the time of the events described.

The name "Ramses" (or "Raamses") is mentioned five times in the Bible. It appears in the context of the ancient city in Lower Egypt, which the Hebrews built as one of the treasury cities³. Here are the references:

- 1. Exodus 1:11 - The Hebrews built the cities of Pithom and Ramses.

- 2. Genesis 47:11 - Joseph settled his family in the land of Ramses.

- 3. Exodus 12:37 - The Israelites set out from Ramses to Succoth.

- 4. Numbers 33:3 - The Israelites departed from Ramses on the fifteenth day of the first month.

- 5. Numbers 33:5 - The Israelites left Ramses and camped at Succoth.

Conclusion:

The oldest version of the biblical book of Exodus from the Torah is the Leningrad Codex, which includes the oldest known complete copy of the Book of Exodus, created in the early 11th century CE. It was written over a thousand years after the reign of Ahomose 1, who reigned from 1570 to 1546 BC.

The biblical account of Moses and "Israel" as the chosen people of God who escaped from slavery in Egypt is not based on historical reality but primarily upon myth and legend. No archaeological or textual evidence supports a large population of "Israelites" in Egypt or their miraculous departure under the leadership of the biblical Moses. On the contrary, there are indications that the name Moses, or Mesu in Egyptian, was a common name among the Egyptians of the 19th dynasty, which coincides with the traditional date of the Exodus. Mesu means "son" or "born" in Egyptian, and it is often used as a suffix in royal names, such as Ramesses (Ra-mesu), Ahmose (Aah-mesu), and Amenmesse (Amen-mesu).

There is no indication that the name "Mesu" (Moses) has any Hebraic origin or connection to the Hebrew verb mashah, meaning "to draw out." The biblical story of Moses being drawn out of the Nile by Pharaoh's daughter and given a Hebrew name is likely a later invention to explain his Egyptian name and role as a liberator of Israel. Moreover, the biblical Israel is not a historical nation but a theological construct that emerged from Nomads within the mountains of Canaan (Tel Hazor), where they also usurped and promoted the Egyptian crescent Moon deity Yah (Yarikh) to their high god over Ausar (Osiris).

The biblical narrative of Israel's origin, history, and destiny is a product of theological imagination and political propaganda, not a historical fact that grew with their dominance in the region. Therefore, it is more plausible that the biblical Moses and Israel are fictional characters based on some historical Mesu who lived in Egypt and Canaan during the 19th dynasty.

|

| Crescent Moon deity Yarikh, which eventually became known as YHWH |

The Errancy of Oral History

The Oral Torah was passed down orally from generation to generation until its contents were finally committed to writing following the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE. The primary repositories of the Oral Torah are the Mishnah and the Gemara, which together form the Talmud, the preeminent text of Rabbinic Judaism. The Mishnah was compiled between 200 and 220 CE by Judah ha-Nasi, while the Gemara consists of running commentaries and debates concerning the Mishnah.

Belief in the Oral Torah being transmitted orally from God to Moses on Biblical Mount Sinai during the Exodus from Egypt is a fundamental tenet of faith in Orthodox Judaism. However, not all branches of Rabbinic-inspired ideologies accept the literal Sinaitic provenance of the Oral Torah. Some characterize it as the product of a historical process of continuing interpretation. Dissenters to the Oral Torah include ancient groups such as Sadducees, Essenes, adherents to modern Karaite Judaism, and Beta Israel.

One of the main challenges with oral history is the reliability and validity of the information obtained. Memories can be fallible; individuals may recall events differently or have gaps in their recollections.

The 1st 5 books of Moses

(Deuteronomy 34:5 says Moses died, but the book continues for several verses..?)

The first five books of the Bible, also known as the Torah or the Five Books of Moses, are traditionally believed to have been told by Moses himself around 1,300 B.C.E. The preservation of these books was initially done orally.

This is the natural and true story of your biblical Moses supplanted with actual facts, not fables from a defeated people.

This is the complete rewrite and realignment of your fabled biblical Exodus matched with actual transcriptions from the walls and papyrus of our sacred MDU NTR, not orally spoken embellished stories. Compared with accurate, peered historical evidence.

Realigned.

Nuwaubian Hotep

Comments are welcome. Disrespect is not. Hotep!

This is a work in progress; please revisit for updates.

.jpeg)